Understanding metal roll forming and its tooling-roll forming machines

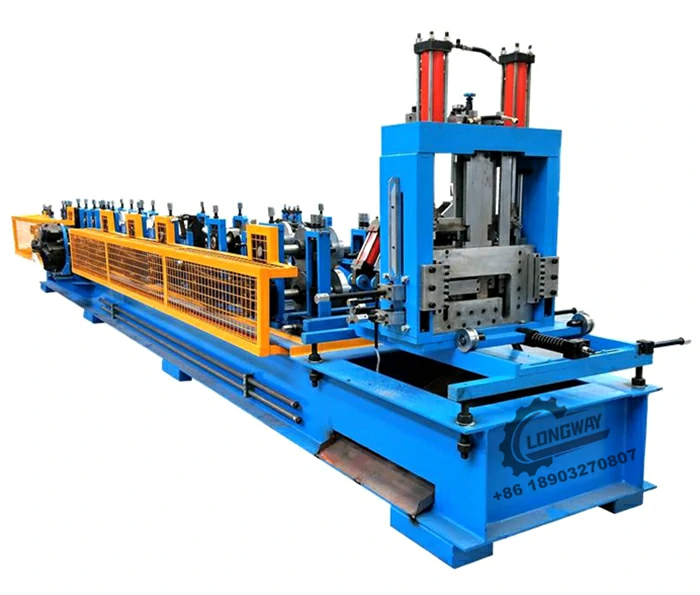

A roll former may appear to be a complex machine, with its array of stations and high speeds. It’s worth learning about how it works because it can perform a unique function and create identical end products consistently that meet the strictest of specifications.

A roll former may appear to be a tremendously complex machine, with its wide array of stations and high speeds. It’s worth learning about how it works because it can perform a unique function and create identical end products consistently that meet the strictest of specifications.

To better understand what the roll forming machine is doing, it’s best to break it down to study each place the metal is changed in some manner--be it bent, punched, cut, or folded.

Roll Form Tooling

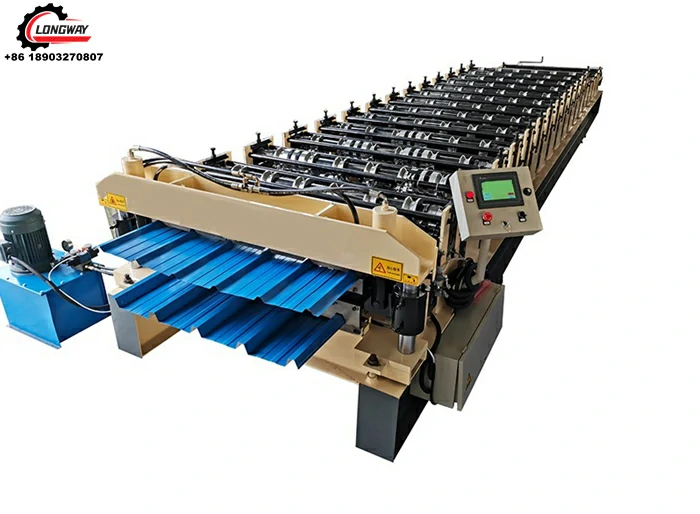

Whenever sheet metal is changed on a roll forming line, the roll former’s tooling progressively alters the metal’s shape. What starts out as coil undergoes any number of changes before a finished product is packaged at the other end.

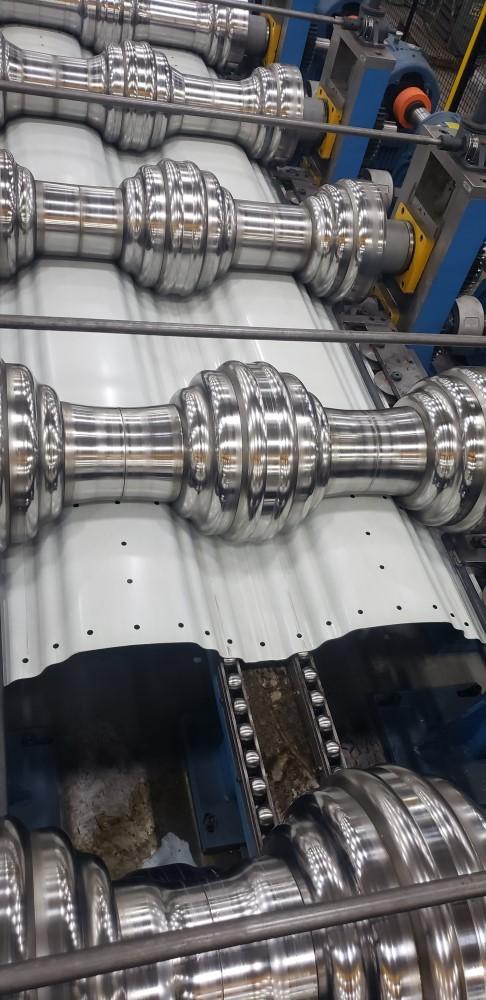

The forming is completed by tool steel rolls as they roll over the work metal. Each roll changes the shape of the sheet metal successively as it advances on the line. Ultimately, as the progression of the desired bend or fold increases, more wheels or dies are required to make it happen.

Increasing the bend progression too fast can damage the material and make it challenging to produce a finished product within tolerances. Increasing the bend progression too slowly results in the need for extra dies or forming points at a higher cost. A machine with more forming points also takes up more space on the shop floor.

Metal Roll Forming Punching and Cutting

A roll forming line can form, punch, and cut a variety of metals in a range of gauges for use in many industries, including construction. It’s important to determine if the metal should be punched before or after it’s formed. Punching it after it’s formed may not always be possible or could be more costly.

The sheet metal can be cut at a specific point on a roll forming line. Determining the best spot to make a cut is important because the end product will be different depending on where the cut takes place.

Either way, fabricators must account for flare and determine how forming affects it. When the roll formed part is cut, some residual stresses that were created during the process are released. This opens or deforms the trailing ends of the part. This is known as end flare. If the part is formed in a precut roll forming process, the stresses could be greater than for a part formed in a postcut roll forming process.

Any time the sheet metal is changed on a roll forming line, it is carried out by the roll former’s tooling. The forming on a roll former occurs as the sheet metal rolls under each steel roll, which changes the metal’s shape successively as it advances on the line. The roll at the top impresses four lines of indentations in the steel, the next rolls form six lines, and the last roll makes those impressions deeper and begins to curve the two raised sections.

Weighing the differences between precut and postcut operations can help determine the best approach.

Precut Pros

- Eliminates expensive cutoff dies and their maintenance.

- Results in burr-free ends.

- Uses a simple, low-maintenance precut shear.

- Allows hand feeding of strips or sheets for low-volume production.

- Prevents cutoff distortion.

Because of the work material’s variable thicknesses, different yield strengths, and elongations during the part formation, it is important to match the radii and other dimensions of the cutoff inserts to the part profile to get a good cut. Conversely, cutting without matching the dimensions can cause distortions. When the part is formed in a precut roll forming process, it is cut flat and, hence, there is no need to worry about matching the profile to the cutoff inserts.

Precut Cons

- Can increase end flare, especially in deeper parts because there is no support for the leading and trailing edges in a roll former.

- Necessitates more overbend in high-strength steels (HSS) because the springback in HSS is higher than in other types of steel and there isn’t any support in the leading and trailing edges.

- Requires more forming stations, making the roll former and tooling more expensive.

- Generally, needs more floor space.

- Makes controlling quality in multibend parts difficult because the additional bends can add more flare.

- Poses a challenge for forming short parts. For a part to move through the roll forming machine, it needs to be engaged in a minimum of two forming stations at all times. The shorter the part, the more challenging it is to engage the part, which can introduce part quality problems.

- May require intermediate guides, especially on short pieces. Adjusting these guides becomes problematic with multiple-width guides.

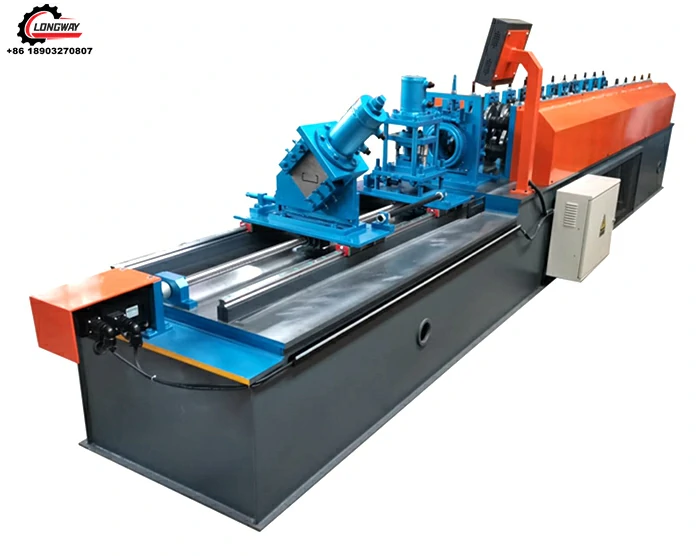

Steel deck floor roll forming machine

Postcut Pros

- Raises production rate because the uncut coil runs continuously through the forming stations. Conversely, in a precut roll forming process, the cut material hits each forming station, so the line speed must be slowed to prevent material buckling and lodging in the machine.

- Facilitates better part control, resulting in better quality. Because the material runs continuously through the machine, the parts are being formed while the material is held in each forming station.

- Reduces end flare considerably because it can be controlled.

- Achieves better results for HSS such as dual-phase and martensitic steels because the leading and trailing edges of the part are held in each forming station.

- Produces lengths as short as 2 to 3 in.

- Allows the use of end straighteners, which are the most effective in postcut, controlling bow, camber, and twist.

- Eliminates leading-edge deformation of the part.

- Extends roll life on heavy-gauge and high-strength material because there is no leading edge to hit the part as exists with precut.

- Is friendlier to material gauge and hardness deviation because the process and lack of a leading edge does not stress the machine or tooling. The parts tend to run smoothly through the machine, as opposed to a precut process.

- Can provide punching/notching during the cutoff operation, possibly eliminating one or more secondary operations.

Postcut Cons

- Can cost more initially because a cutoff press and die can be expensive.

- Adds maintenance costs, especially for the cutoff die.

- Causes end burr and rough ends.

- Creates distortion on product ends.

- May require manual feeding of the leading end of the first part when a new coil is introduced.

- Requires all surfaces to be supported to avoid end distortion in many cases. This is not possible if robust die sections cannot be built into the die or if an opening must be left in a closed space.

It’s important to determine if the sheet metal should be punched before or after it’s formed (top). This is precut.

Metal Roll Forming Bowing, Camber and Twist

Metal imperfections are common and can create problems during the roll forming process. They can even occur during the roll forming process.

Using tension-leveled steel or aluminum coil helps. Tension leveling is the process of pulling metal beyond its yield point to permanently alter its shape and make it flat.

Any roll forming action can cause imperfections, so it’s important to make sure your machine is operating correctly and that every change your machine makes to the metal is within the acceptable tolerances–from beginning to end. For example, a misaligned entry guide can cause imperfections.

Fortunately, bow, camber, and twist can be straightened out, literally, during the roll forming process. A straightener can be part of the line. It should be located as close as possible to the last forming process. Even straightening induces tension on the metal, so it’s best not to use a straightener if it’s not needed.

Tooling Cooling

Today’s roll formers operate faster than ever, and odds are that, moving forward, demands will be to operate even faster. The problem is that when material runs at high speeds, it heats up drastically and can change shape. There are a couple ways to try to moderate the temperature to prevent material changes.

Flood cooling extends tooling life, but it is messy. Dry cooling is cleaner than flood cooling, but it shortens tooling life. That, in turn, changes the shape of the end product.

Tooling Steel

Every work material reacts differently to the stresses of roll forming. Some materials are more malleable, or softer, than others. Soft materials may require fewer bending stations. Black steel, galvanized steel, prepainted steel, stainless steel, aluminum, copper, and brass all react differently in the roll forming process.

It’s important to determine if the sheet metal should be punched before or after it’s formed. This is post cut.

The type of roll tooling steel--4140, D2, 52100, or O1--and the postprocesses used on it, such as hardening or chrome plating, vary based on the type of work material the rolls are forming. Each gets hardened differently. Experienced roll former OEMs know these characteristics and can provide the best tooling design accordingly.

Rafted System

In a rafted system, the tooling is already loaded on the shafts. A station of multiple passes will be preloaded and preset. When a fabricator needs to change from one profile to another, it does not need to change the entire tooling. All it needs to do is lift a raft using a forklift or an overhead crane to remove the raft with the previous profile and replace it with the raft of the second profile.

Rafted System Advantages:

- Reduces mistakes that could be made by an operator during manual changing of the roll tooling; the roll tooling for the different profiles is already set on the rafts.

- Lowers the possibility that the operator may not set the gap correctly because it is preset.

- Helps to reduce changeover times. Depending on the type of profile and the number of raft sets, experienced professionals can change from one tooling to another in 30 to 45 minutes versus hours or days.

Metal Roll Forming Safety

Because today’s roll forming machines operate at high speeds, it’s important to understand their built-in safety features. It may seem obvious, but it’s important to keep the safety equipment (guards, covers, and so forth) in place, whether the machine runs with or without an operator.

Safety awareness should include thorough training on the roll former and any complementary equipment. It’s important for the operator to understand the ins and outs of every operation up and down the line--both to be safe and to operate the machine efficiently. Special attention should be paid to tool changes or machine adjustments. Any quality fabrication shop will have a safety plan in place that covers the roll former and other equipment. Creating a safe place for employees should be at the top of the list.

-

Roof Panel Machines: Buying Guide, Types, and PricingNewsJul.04, 2025

-

Purlin Machines: Types, Features, and Pricing GuideNewsJul.04, 2025

-

Metal Embossing Machines: Types, Applications, and Buying GuideNewsJul.04, 2025

-

Gutter Machines: Features, Types, and Cost BreakdownNewsJul.04, 2025

-

Cut to Length Line: Overview, Equipment, and Buying GuideNewsJul.04, 2025

-

Auto Stacker: Features, Applications, and Cost BreakdownNewsJul.04, 2025

-

Top Drywall Profile Machine Models for SaleNewsJun.05, 2025